The New Zealand Southern Alps

Although New Zealand is an island nation in the Pacific Ocean, it is renowned for its mountainous geological structure. The element of this island that is even stranger is the fact that it is part of a much larger continent which is mainly submerged beneath the ocean. What is visible to the human eye on the surface is a vast array of mountains and cliffs immediately next to the ocean with rolling hills interrupting peaceful valleys. Underneath all the tranquility, who would guess that the movement beneath the crust creates chaos above and below?

Drone Footage of New Zealand's Geological Features (Wild Atlas, 2016)

The two islands that make up the nation of New Zealand lies East of Australia and South of other well known Pacific islands such as Fiji. Geologically, it is a product of the intersect and interaction between the Pacific Plate and the Australian Plate. Once a part of the ancient continent of Gondwana, New Zealand broke off from Australia and Antarctica.

On a geographical tour, I would inspect the impressive mountain ranges that have been pushed up by the pressure between the Australian and Pacific plates. I would be able to find a wide variety of kinds of rocks including sedimentary and igneous. If a tourist were to collect rocks as a way of exploring the geological history of this nation, one would collect granite, sandstone, greywacke, and mineral filled schist.

|

| Illustration of the fault across the North and South islands of New Zealand (University of Otago, 2018) |

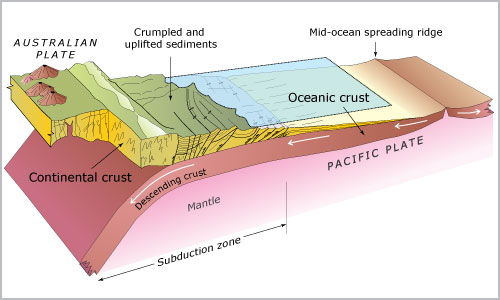

The overall structure of New Zealand rock varies. Because the Pacific plate puts compression stress against the Australian plate and then sinks beneath it, the faults that are caused are oblique thrust faults. The Northern island and the Eastern side of the Southern island are made up of rock that was folded and then broken and raised up into massive mountains made of rock material that is known locally as greywacke. On top of this layer in areas that are not as raised up lies a bed of relatively recently deposited sedimentary rock. This is clearly the result of the pressure from the mid-ocean spreading over millions of years. The Western side of the Southern island, just on the other side of the Alpine fault, is built on much older igneous rock. There is evidence that the Alpine fault over the course of millions of years has pushed apart existing granitic rock formations leaving each half on opposite sides of the island entirely.

|

| Diagram of the movement of crust between the Pacific Plate and the Australian plate (McSaveney and Nathan, 2006) |

Although the surface seems tranquil, the island itself is constantly changing geographically as it has been for millions of years. The mountains have continued to rise up further and the valleys have been slowly filled up by the ocean. Perhaps someday this island will have no valley to speak of, no tourist sites of the filming of The Lord of the Rings, no herds of grazing sheep, but will be merely a stately mountain range rising above the tides.

Sources

Lutgens, F. K, Tarbuck, E. J., & Tasa, D. (2016). Essentials of geology. (13th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall (Pearson).

University of Otago. (2018). Tectonic setting of New Zealand: Astride a plate boundary which includes the Alpine Fault. Retrieved November 21, 2018, from https://www.otago.ac.nz/geology/research/structural-geology/alpine-fault/nz-tectonics.html

No comments:

Post a Comment